Elite Sport: Health is Wealth & Why Wingers Highlight the Profligacy of Football

The demands of modern sport have created a new type of athlete intent on cultivating a performance by conditioning & how wingers are becoming the poster children for overspending

Footballers look after themselves pretty well these days. They don’t really have a choice. The demands of the modern game are unforgiving; there is little chance you can perform at the top level and satisfy an ill-advised craving.

But this hasn’t always been the case. The level of professionalism (with regards to health) goes hand in hand with the quality of product football and the commercial muscle of Europe’s top leagues.

Beers, burgers and cigarettes have been replaced with kale, quinoa and smoothies (or a cow heart if you ask Erling Haaland).

You don’t need to be a genius to know why this has happened. But what has a shift in consumption habits actually enabled athletes to achieve beyond just being fitter?

This week’s guest is the premium advocate for knowing the value of what you consume…

Thomas Hal Robson-Kanu didn’t rely on anyone to fix his career threatening injuries sustained as a teenager. Alongside his Dad, they created turmeric based remedies to tackle the inflammation he couldn’t combat through ‘traditional’ treatment and medication.

Necessity is the mother of invention; we have all heard it but what does it really mean? In Hal’s case, it meant playing 476 games for club and country or not. He is convinced that if it wasn’t for turmeric he wouldn’t have made it out of the injury nightmare every player dreads.

But as highlighted in this week’s show, players looking after their bodies and approaching the sport as an Olympian approaches their discipline is a relatively new (in the lifespan of football) concept.

And there was one major change agent…

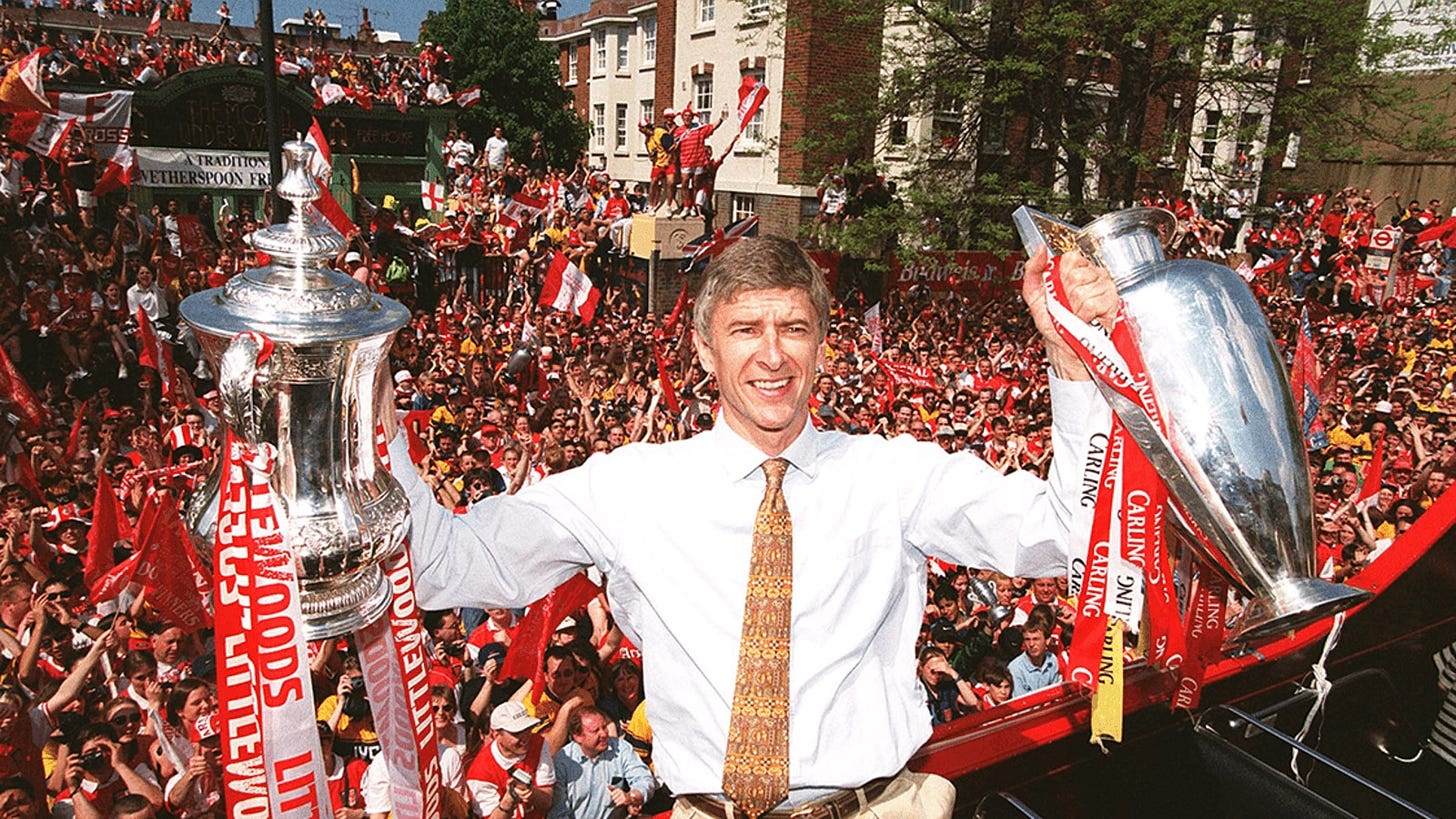

Arsène Wenger was all around attention to detail. He was one of the first managers who brought nutrition, health, wellness into the mind's eye of the English League, realise that actually if you looked after your body, your levels of performance could improve. Obviously that's because you're recovering quicker, you're in better condition, so you work harder and get better results.

Hal Robson-Kanu —

When Arsène Wenger arrived at Arsenal in 1996, English football was still entrenched in a culture that lionised hard tackles, celebrated post-match beers, and considered pasta a foreign concept. The Premier League, though brimming with talent and passion, was behind in one crucial aspect: how players treated their bodies off the pitch. Wenger, with his quiet demeanour and academic air, came not only to win trophies, but to change habits and cultural fundamentals.

Full English, Full-Time

In the 1980s and early '90s, most Premier League clubs lacked formalised nutritional structures. Matchday prep might include fried breakfasts, and post-game meals often meant curries and lager. Recovery was misunderstood, hydration was an afterthought, and performance science barely existed in club setups. Players largely managed their own routines with minimal guidance. Fitness and diet were viewed as matters of personal discipline, not club-driven science.

The result? Premier League players often burned out early or carried chronic injuries. Longevity was rare. Energy levels fluctuated. Technical improvements on the pitch were hindered by what happened off it.

Wenger’s Arsenal: Red Wine to Regimens

When Wenger took over Arsenal, he brought not just a continental tactical philosophy but a sweeping change in professionalism. He eliminated junk food at the training ground, banned sugary snacks, and brought in club chefs to cook lean protein-rich meals. Supplements were introduced, hydration was monitored, and weigh-ins became regular.

He worked closely with physios and fitness coaches to tailor diet plans to individual players. Pre-game meals shifted to include more complex carbohydrates. Red wine at lunch (really!) disappeared.

Players were encouraged to sleep more, stretch regularly, and think of recovery as an extension of training.

There was resistance. Veteran players scoffed at “all the broccoli.” But within a season, the squad looked fitter, injuries declined, and Arsenal started to play a more fluid, relentless style. The proof was in the performance: a Double in 1997–98, then the historic Invincibles season in 2003–04.

Wenger didn’t just win matches, he extended careers. Players like Dennis Bergkamp, Thierry Henry, and Robert Pirès remained top-level into their mid-30s.

Sports Science Goes Mainstream

Wenger’s methods drew headlines and attention. Soon, rival clubs hired nutritionists, performance analysts, and sports scientists. Manchester United, initially skeptical, eventually adopted similar approaches under Ferguson, especially as competition intensified.

By the early 2010s, every Premier League club had bespoke nutritional setups. Kitchens were redesigned at training grounds. Players underwent regular blood tests, and wearable tech tracked sleep and hydration. Clubs like Manchester City and Liverpool embedded cutting-edge research into their recovery protocols: cryotherapy chambers, altitude rooms, and AI-powered diet plans.

Wenger’s influence was clear: the modern Premier League athlete eats, trains, and recovers like an Olympian. Gone are the days of post-match pints. Today’s stars drink protein smoothies, follow bespoke anti-inflammatory diets, and track their macros as obsessively as their minutes played.

The impact goes beyond food. The modern footballer’s body is leaner, stronger, and more explosive. The average distance covered per game has increased. Injuries are managed with greater precision. Clubs now invest in preventative care rather than reactive treatment.

And it's not just about keeping players fit; nutrition has become a tool for competitive advantage. Marginal gains are everything. When Liverpool hired expert Mona Nemmer from Bayern Munich, Jürgen Klopp called her “our most important signing”. And of course, it makes for better business!

Wenger often said, “To be a footballer is to live like a monk.” He didn’t mean it as punishment, but as an invitation to treat the body with reverence. He made food and conditioning part of football intelligence, just as important as positioning or passing.

Today, Premier League clubs resemble high-performance labs. Players enjoy longer careers, greater consistency, and faster recoveries. As Hal has showed through his work creating the Turmeric Co, players are absolutely entrenched in this ideal. It is top to bottom.

In changing how clubs and players approached health and nutrition, Wenger didn’t just change Arsenal, he changed the game, making the Premier League and it’s key protagonists one of the most valuable sporting ecosystems in the business.

OPINION PIECE

Wingers: football’s NFT boom, but this time there’s no sign of a bubble bursting.

Nothing signifies footballs penchant for spending like billionaires on millionaires income than this insatiable thirst for the touchline huggers.

This is not a critique on the talent of Madueke/Gittens/Kudus/Elanga…on the contrary. They’re good players who have impressed on occasion. But that’s just it. ‘On occasion’. Does that make these players worth £50m? I don’t think so…

But then what does justify £50m? And what does worth actually mean in 2025? The uncontrollable inflation of transfer fees and wages has made the ‘is he really worth ‘x’’ argument a futile waste of oxygen.

Value is in the eye of the beholder; Elanga is worth what someone is willing to pay. No one is forcing Newcastle’s hand. We are now in an environment where clubs are fuelling each other's irresponsible approach to deal-making; precedent is the dominant force of boardroom negotiation.

Elanga’s move to Newcastle would have set the bar for Madueke’s to Arsenal. “If Anthony’s gone for £55m, Noni is worth at least that”.

But what if Forest have pulled a blinder and got Newcastle to pay way over the odds? Doesn’t matter. The new bar height is set, and now every club lines up to try and clear it.

This vicious circle is so hard to break because clubs are on both the buy and sell side. Selling clubs know buyers are flush with cash, and they price assets accordingly. Buying clubs may well have traded another player for a similar sum and therefore have normalised a fee that is beyond the realms of sensibility.

Central midfielders are also trading like blue diamonds, but when the Caicedo and Rice money is spent, it does seem to be on a smaller cohort with far more clarity on the desired performance influence. It doesn’t mean the price isn’t frighteningly impactful in establishing the ‘new value’ of a top midfielder, but let’s stick on wingers.

Anthony (£85m), Mudryk (£88m), Sancho (£75m)...you get the point.

There needs to be a realignment of what value means across football. The business models of even the biggest clubs have not earned the right to spend what is becoming the norm on players. The new regulations meaning a club can spend 85% of their revenue on player costs shouldn’t be celebrated either. That leaves 15% to spend on everything else before running in the red. 15% is not enough to cover those costs. Fiscal responsibility and prudent practice? Nope.

Winger inflation is understandable though:

Last season, 5 of the 10 top scorers in the Premier League were wingers.

7 of the top 10 assists providers.

Tactics are now built around width, inversion, five-lane attacking systems.

Wingers aren’t just crossing machines anymore; they’re pseudo no10’s and secondary strikers. Vinícius, Salah, Saka, Son….not the wingers of past generations. They’re match-winners who look to cut in, create and score. If you’re looking to spend big, why not spend big on a player that’s going to have more of an impact on your attacking game than any other.

And with match influence comes brand, shirt sales, iconisation. So when dissecting these numbers, the validation comes from impact on and off the pitch. These are the players with the most ‘value’ to the modern club and wider game. That makes sense.

But this financial model to acquire such talent does not; not when the income is so far outweighed by expenditure. Budgets should align with what an asset generates. If all clubs took this approach, the market would reflect it…

Because value is derived from what someone is willing to pay.

If there’s no market at £50m it moves to the price level to where there is a market. Clubs need to do business! And right now, few clubs are getting close to generating what is required to spend £50m+ on multiple players and operate as a sustainable business.

Which is all well and good…until the cash taps are turned off.

Want to see more from Business of Sport? Visit us across our various platforms linktr.ee/bizofsport

And of course a huge thank you to our amazing partners on the show:

RUNNA

Whether you’re an existing use or if it’s your first time on the app, use the code below for exclusive access!

https://join.runna.com/lKmc/redeem?code=BOSRUNNA

AND

You can get your hands on some of the awesome Turmeric Co products here with our special code BIS30 for 30% off of orders!